The Doge of Flatbush

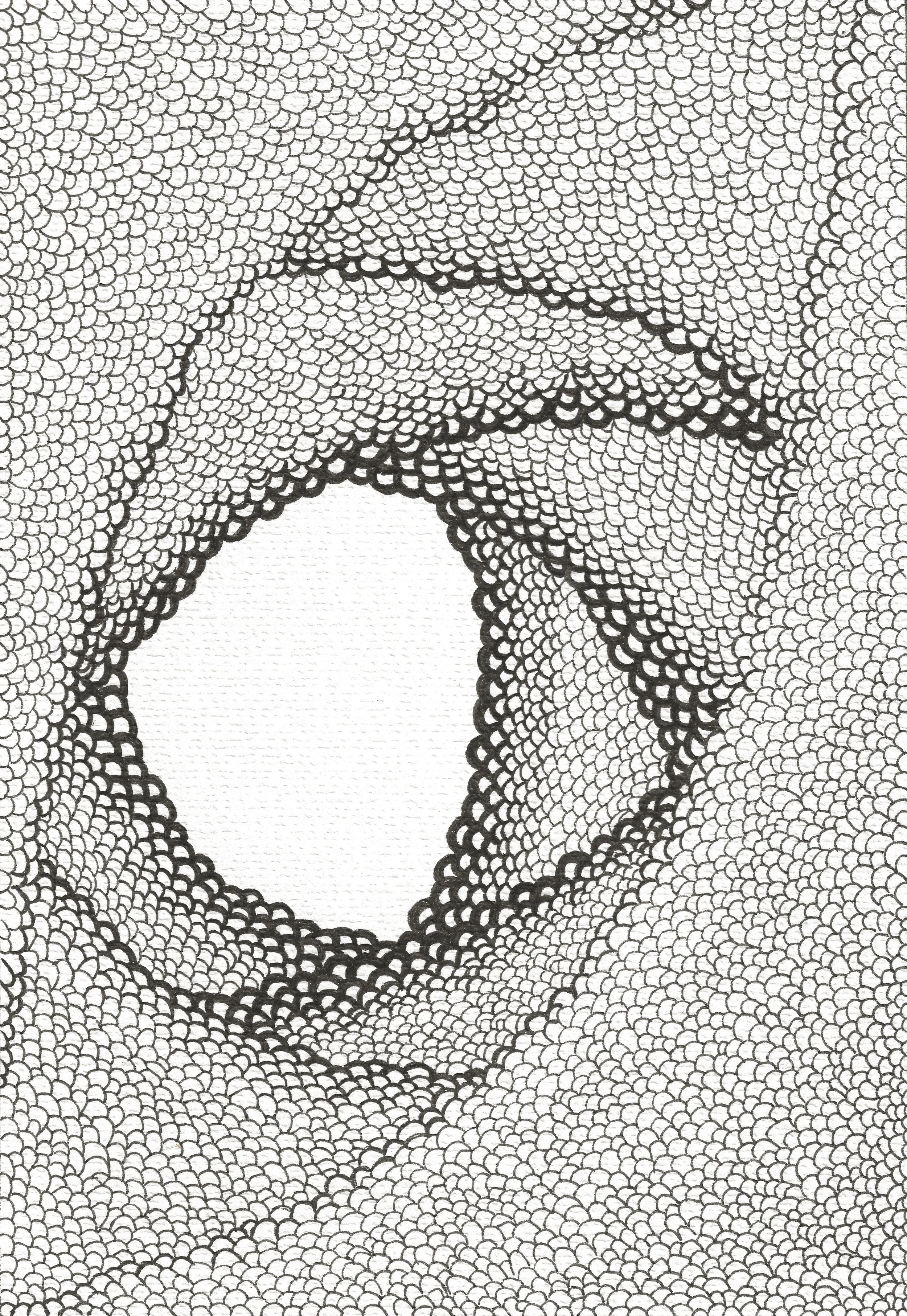

“In Pursuit of Eurydice” by Haley Cole

Every twenty years, I fly to Venice. It used to be an empire. A Republic.

***

There are many places here where you are not. One is the stone spiral staircase to my apartment. An obelisk used to walk these stairs, a rectangular giant that swung corner over corner to navigate the radius. This explains the dents in the iron handrail. In a bedroom, the obelisk slept, wondering why someone had created a wooden staircase up the wall, leading to nothing.

I am twenty years old. In the frigid streets of Montreal, I used to walk without a jacket, making music by crunching the salt chunks beneath my sneakers. Wear better shoes, people told me. Put on a scarf. We hope you get better. People passed me in the airport on the way here, hoping that I would get better. On the plane, the stewardess. On the wing, ears between his knees, the old man in the robe.

I meet you in a bakery along a canal, where flies buzz over the pastries behind the glass case. So many flies around a golden robot vintage espresso machine with spigots and protrusions that look like they are meant for extraction. Give me your money, it demands with a hiss of steam and a rattle of its sick head.

“An almond one, please,” you say to the server.

You sit at the front of the shop. Outside, a garbage skiff waits next to a collection of bins, each soliciting a different flavour of waste.

“I’m Ruth,” you tell me.

“I’m Jatinder.” I inform you within two minutes that I’m unwell, and that’s why I have no relationships.

“Why are you telling me this?” you ask.

“I found out in New York, on a school trip. We were in Flatbush, a small part of Brooklyn. We’d gone there to learn. We’d gone there to get better. I was in the shower, and music was playing. It was perfect. But I was late for the city walk. The time change had come, and I had lost an hour. I looked for it in the bedroom. On the sidewalk. But it was gone. I didn’t find the group that day, so I wandered the city alone. Flatbush. It’s small, and dying, and I told them so, that this place is going to end. After that, they said I was unwell.”

“What do you think was in that hour?”

I drink coffee because life is good. “Wellness.”

Venice doesn’t smell, I explain. I invite you to inhale as we walk. We cross five bridges, which is all it takes to become lost. We eat nero di seppia under an umbrella beneath rows and columns of shuttered windows, all yellow and glowing, as though they have been digitized.

“Cuttlefish ink,” you tell me, as you chew. “That’s why it’s so dark.”

“We’re eating ink,” I say.

“What does that make us to each other?”

A bottle of wine comes, and goes. The sun creeps underneath the umbrella as school children let out and savage a soccer ball against the closed front of a repair shop.

You lead me through the streets and over Ponte dell’Accademia, our footsteps clacking against the wood, the garbage lined up against the guards that prevent it from slipping into the Grand Canal. We head east. I explain that Venice was once a Republic.

“Tell me,” you tell me.

“Venice ruled Cyprus. The large island near Lebanon. To get there, you have to go past Sicily. Past the mainland of Greece. Past even the island of Rhodes. It’s so far away from Venice, but they ruled it. The Doges ruled it.”

“I saw the end of the Republic. I was there.” Then: “Doges don’t rule. They only reign.”

“That’s right,” I tell you, the sweat slipping to my slippers as they slap the cobbles. Men and women in white shirts beckon us to enter their restaurants. “Venice had a great sea army. They owned lands that now belong to seven countries. It was a Republic, one of the strongest, for a thousand years. Today, it is a place for tourists.”

“Like you.”

“And you,” I return, but you tell me to be quiet, for we have arrived.

‘We have arrived.’ I saw those words when I graduated high school. Every kid had it imprinted on their faces, traced by dangling hair, etched in fine cursive across their eyeballs. I hiked Montreal in the summer after school was finished, up the slope of Mont Royal until I reached the cross at the top, its glowing shell surrounded by forest. I just wanted to find a friend, but Montreal was too small for that. Too new. I had to look elsewhere.

“Libreria Acqua Alta,” you tell me. The laneway is so narrow that it is hard to navigate past the tourists. We smell their sunscreen and wine breath. Once, there were a few hundred thousand people in this land that was a Republic; now, there are less than fifty thousand. Every year, a thousand people leave. Every year, a thousand people diffuse into the world.

A bookstore. There is a boat on the floor in the middle, and on every wall, stacks of books. No organization to the titles. Some are old, some new, and some are rusted in the rain. You pick one up and tell me you’ve already read it, have I? Then another, and you tell me that you’re acquainted with it, too.

“But what I want to show you is there,” you say.

At the back of the shop, there is a courtyard. Against the wall, books. They have been arranged to make stairs, leading to a platform against the back wall. Children are standing on the construct, as parents in their sunhats take photos.

We wait in line until the passage clears. We climb books. We stand on the platform, books piled underneath it. I already know what you will say: I have finally reached Venice, where this courtyard holds residence, on the other side a canal with gondolas and speedboats, coexisting in the grey-green water as an old man sits on a balcony and sips coffee. We wave at him, and he tells us: you have arrived. You have both, here, arrived.

***

At the top of the stone staircase to my apartment, there is a carving of a man. He looks up and to the side, black dots in the middle of his retinas to tell me so. He has a moustache like a highway chevron and wears a turban. It is a careful turban, wrapped with precision, the folds a lattice of desiccated cookie dough.

I take a shower. The water is hot, as though it floods upwards from the canals through counterfeit pipes to wash the inhabitants of this city. I think of you in Venice, both of us unproductive humans, here doing the most human of activities: exploring, growing, learning. Making friends. What is it to make a friend, when the chances of you being together again are so slim? I don’t even know where you are from. You haven’t told me. I don’t know about your family. You may not have one.

I step out of the shower. Outside, a man in a turban is looking up and to the side, the same thing he has been doing for a thousand years. I go to him naked. The man in the turban saw it, the obelisk that stayed here, back in the time when this city ruled, and the Doges reigned.

***

Along a canal, we find a restaurant. Boats play music, ripples colliding with the rock below our sandals. I wonder if a prehistoric version of Venice ever froze.

Drinking Aperol spritz, I tell you that I loved the bookshop, even though I bought nothing, and you kept telling me that you had read everything. Over a dish of cold, pickled fish, we entertain the idea of gelato, each of us telling the other that we know the best place. But it’s through wine that we become friends. The sips are so sweet that it can’t be anything but friends, and by the end of the barolo, with its tough oak and leafy must, it’s sealed. An unlikely, non-productive, nascent friendship. I tell you it is the one thing I didn’t think I would find here. You tell me yes, we should go for gelato.

We hold hands, but it’s not that type of moment.

“It was the most serene Republic,” you tell me. “But it was a Republic. I remember.”

“You remember?”

The gelato steams. If gelato doesn’t steam, then it is not good enough. It must be that cold to preserve its flavour and texture. I take lemon and pineapple. You have coconut with another scoop of coconut.

“The last Doge was Ludovico Manin,” you tell me. “He didn’t want the dogate, but no one else wanted it, either. It was 1789. A hot summer. Austria and France were fighting. Napoleon was on his way. Ludovico abdicated, for he knew that the Republic had ended, that the fate of the city was for its people to leave, a thousand at a time. I don’t blame him. Don’t blame Ludovico. I saw him later, in Tunisia. He had an apple farm, but I think he grew dates, too.”

“Ah,” I say. You are my age, I think to myself, with your blue eyes and light hair, your clothes that define your bare arms.

There is a lightshow on the walls of the Palazzo Ducale, the once-home of the Doges. The Doges of Venice. I wonder if there was ever a Doge of Montreal. Or of Manitoba. Or a Doge of Flatbush. The Doges started like kings, until the wealthy took their power. By the end, Doges ruled but no longer reigned. They wore the trappings but had no authority. They lived in a Palace but had no sway. In this, they are like a young man and a young woman walking the canals. Five bridges, and they are lost. Doges of the modern era.

In St. Mark’s square, a hundred lit-up rubber band helicopters are rising. Vendors step around tourists to snatch their demonstrations from the air, and to offer them up for a few Euros. Children say please. Once, there were pickpockets, but the credit card killed the pickpocket in a way the polizia could never have done. I dance with you, for music is playing, but it is not that kind of dance. It wobbles and collides, bodies flying and combining. Later, we buy a helicopter that is so much harder to launch than we had thought, until we get it right and it flies so high.

At night, wine with bread and garlic oil. You tell me that you have to tell me something.

Friends. That is all I need. The hope that we will meet again, here or somewhere else. In the humid heat, people drink beer and wine and spritzes. Let’s drink, too.

“I’m serious,” you tell me.

I lean in. I listen.

***

“People think of God as apathetic, or that God has left all decisions to people,” you say.

“I don’t believe in God.”

“Then why are you in Venice?”

“All the reasons that are not God. Plus, it’s better than Montreal.”

“God is also not vengeful or angry or wicked.”

“If God were like that, Venice would be sinking.”

“That’s not a funny joke. There is one other possibility: that God took on too much. That God chewed more than God could swallow. That there are too many civilizations to take care of, and not enough time to tend them. Even God gets tired.”

“Does God need a nap?”

“God doesn’t sleep. But God can be overextended. God can be anxious. God can see civilizations across the universe coming apart. Peoples are leaving, a million at a time, to find a new home. A new world. God can see it happening, but how could God tend to it all?”

“You’re saying that God is overworked.”

“It’s of my own doing. Starting too many stories in too many places. I am Ruth. You are a Brown unwell boy from Montreal. The last time I was in Venice, Ludovico Manin was abdicating. It was the end of the Republic. I sat in a palazzo and watched the rain come through the roof, slipping through a hole it had carved in the floor, dropping to the basement where it entered the canal. I thought: what a tortuous path for those droplets to make their way back to the water. What an awful thing for the madness to come like that, degrading the Republic. I could have done something about it, but I was tired. I was overwhelmed.”

“That was two hundred years ago, Ruth,” I say to her. She nods, as though it’s nothing. As though she is well. “You didn’t help Ludovico. What is it you said? He went to farm apples.”

“And dates. Wonderful dates. He died happy. Civilizations end quietly. No world ever blew itself to pieces. No people were ever so stupid as to kill themselves in a moment of ignorance. It takes time.”

“I’m declining. Everyone says so. I’m unwell.”

“You’re twenty.”

“I just want a friend, Ruth. That’s all.”

“And I just want to rest. To have respite from the civilizations that need me. I want wine, gelato, pickled red onions, and the dream that pizza here is any good, even though they won’t let you bake it in woodfired ovens. I am here for the canals and the Doges. For the lightshow on the Palazzo Ducale, and the ferries along the Grand Canal, and how much better the views are of the bridges when you are on the water. I am here to see these things, while they last, because beauty can expire. People are leaving Venice all the time. They want to see the bigger world, as though it is better than this. Venice is sinking. Venice is floating. There will come a time when it does neither. I’ve seen that before. It will happen here, too.”

“What will happen?” I ask you.

“Come back again, now and then. You’ll see. One day, there will be no water in Venice. Maybe I will stop it. Or maybe I’ll be too tired to try.”

Fireworks streak. Ripples bounce. A church bell moves in the breeze, tempted to ring.

I look at you, the light hair, the blue eyes. You are talking about other worlds, and what happened to them. You are explaining how difficult it is to be there for them, as though you are responsible for lives that I will never see, in reaches of the cosmos that I will never visit. They say I am unwell, but you think you are God. A tired, despairing God that finds refuge in a city that will one day run out of water. A firework blows close to the square in which we drink. The sulfur of its demise settles like a cloud on our heads.

Why not just say goodbye? Isn’t that easier?

When I graduated, people gave me advice. Move to Ontario, where there are more jobs. Take a year off. Sort yourself out or solidify your lack of human productivity. Find a friend. Lose a friend. Drink limoncello in your underwear.

Later that night I stand beside the concrete man in the turban. There is no record of who he is. He stares up and to the right. Who knows what he sees, or when he first saw it?

***

“It’s a lot,” you tell me at the train station.

I have a blue backpack with shining zippers. “I hope you get home safe, Ruth.”

“Next week, I’m leaving.”

We stand near the swing gates for the platforms. Here, there are thieves. They can’t pick pockets anymore, but they can steal bags. Tic-tac-toe squares of people bend and elongate in the station, twirling in a dance of muffled announcements and spilled coffee.

“You don’t have to believe,” you tell me. “But I wanted someone to hear. I told you who I am, and now you know.”

I hope you find help, Ruth. “Now I know.”

“That’s your train,” you tell me.

I give her my hand, but it’s not that kind of moment. It’s not any kind of moment, amongst the dented luggage and stickered guitar cases and rainbow umbrellas. Goodbye, you tell me, with those shining eyes. We’ve spent four days together in Venice, and because of you I know where that bookshop is.

The train, when it leaves, reaches an impossible speed. It’s unimaginable.

***

I’m forty. It’s the hottest summer on record in Venice. A haze comes off the canals in the mornings. This is just the beginning of the heat, they say, as though the real crisis isn’t here yet. Droplets at a time, the canals evaporate.

Dogs bark, and later as I take a taxi to Murano, I nap on a wooden bench. Since the last time I was here, thousands of Venetians have left forever. On the canals and bridges, I search for Ruth, so that I can ask her if this is the crisis, if this is what she was talking about, the heat and the lowering water levels, the humidity that drives away all but the hardiest tourists.

Oleg’s legs were cut off by a machine that makes the globes people put around lightbulbs to make them look less like lightbulbs. We met three weeks ago at the hotel bar, each of us with a cooled limoncello on the knotted surface of a wooden counter. He told me that this heat was foretold, but he loved it, the warmth, the quietness of the canals now that people had stopped coming.

I ask him if it’s risky to be in a wheelchair in Venice, taking boats.

“You think people know how to swim just because they have two legs and two arms?” he says, as I push him along a street.

Murano is less busy than Venice.

“They sent the glassblowers here because Venice is combustible,” he tells me as we travel. “But they kept the secrets. If glassblowers tried to leave Murano, the Venetians would follow them into Europe and assassinate them. More glassblowers have been assassinated in Europe than have been politicians. A bad trade, eh?”

We stop in a shop for a demonstration. Oleg watches in fascination as people blow glass.

Later, we go to an air-conditioned hotel. “With your money, you should have a wife,” Oleg tells me.

“Do you want to be my wife?”

He growls, “It would take more than money to make that happen.”

Each fried dumpling of fish is a moon rock. There are pebbles in this food, sand in the wine. We’re twenty years further from the Venetian Republic.

“Why do you come all the way to Venice to make friends?” Oleg asks. “It’s unnatural.”

I’m unwell, I tell him. This has been the prognosis of an entire lifetime, first made when I was half this age. It started in New York, Flatbush, when I lost an hour and couldn’t find it. We all lose that time, Oleg tells me. And we all get it back. It sums to zero.

I laugh and tell him our conversations sum to zero as well.

“I know how to help you,” he says. His voice gets deeper the more he drinks. “We invade Cyprus. Take it back. Egypt, Persia, Greece, Rome, they all owned that place along the line, but no one knows that Venice has a claim, too. A strong one. We take it.”

“An invasion?” I ask, sweating in the air conditioning. The front door opens, and fingers of heat crawl inside, self-destructing into droplets upon contact with the cooled air. Humid chill is the worst chill, says a boy from Montreal who will never go back there, ever.

“Are you with me, Indian? You say you’re Canadian, but I see Indian. I’ve been to your India. It gets cold in the north, hot everywhere else. Let’s give it a run. Five hundred Venetians, that’s all it takes. We’ll assemble the diaspora and promise a new Venice on Cyprus, but this time we’ll do it right.”

“And what would my role be?”

“You?” He sips espresso delivered by a silver robot on a cart. He makes a gesture over his head, as if wearing a hat with a curved hump at the back. “You would be the Doge. The Doge of Cyprus.”

“Reign but not rule?”

He doesn’t smile much, but the espresso is so good.

There are steep places in proximity to the Rialto Bridge. I push Oleg up them. The laneway we find ourselves in is narrow. One shop sells rubber ducks. It’s all they sell, but I never see a rubber duck in the canals, and if I did, I imagine that it would melt and become a slick on the water, torn apart by the boats.

The Libreria Acqua Alta is full of people. Oleg tells me to part the way for him. Attenzione! I cry, as I stride with my graying hair and the aspect of a man who has an umbrella in his hand and is willing to use it. Oleg barks, reading the titles of books, ready to buy them with his meagre pension.

In the back, the staircase of books is still there, but erosion has taken its toll. Mountains erode, so do cliffs, and even buildings fall apart. In Venice’s case, they sink. But in the courtyard, an erosion is occurring too, flecks of paper coming off the books a letter at a time, to congregate on the ground. If we put these together, I wonder, what book would they make? What novel rests on the cobbles, undiscovered by this country?

Oleg doesn’t ask me to carry him up the book-steps, thank God. We take photos for the tourists, families sweating as they stand on the platform, not worried at all that we will run off with their phones, because everything is saved in the sky now, and people in wheelchairs can’t run.

Later, limoncello made with cream, chilled to arctic levels.

“It’s only going to get hotter,” says Oleg.

“Will you leave?”

“Leave Venice?” he laughs. “Is there another city?”

“Many.”

“Name one,” he says.

The day before I leave , I go to the old apartment and ask if I can go in. A cleaning lady admits me, and I climb that spiral stone staircase. I feel like an obelisk, shimmying my corners one after the other. At the top, the light is coming in from windows on both sides. I turn to look at the arch through which I entered, and there he is, the man in the turban with the triangle moustache. He hasn’t changed at all.

***

Venice is cold. Not cold like my memories of Montreal, but the chill has arrived. After all this time, the cold came. I’m eighty. I use a cane to walk over the bridges.

The palazzo leaks. I bought it when I was sixty, so that I could have a winter home in Europe. The heat wave had ended, and everyone said that one day, it might get cold. I didn’t listen. Venice is sinking, I thought. Now, snow melts on the roof and the water dribbles back to the canal as the cold takes its rest here, in this place that once was a Republic.

In his nursing home, Oleg babbles about weather. I bring him pastries. He tells me I should have married, and now it’s too late. I’m unproductive, I tell him. Always have been.

Every bridge is a curve to a peak. It’s harder to descend than to walk up. At each, I spend a moment with the coolness of the water below, the ripples thick. They sell scarves in Venice. They vend gloves, hats, whatever you need to stay warm.

Oleg passes in November. His last sip is wine. His last crumb is a nick of an almond croissant. He tells me I’m his only friend. I pay for his burial on the mainland.

This will be my first winter in Venice.

It gets colder. But the moment of the change in time hurtles us over the edge. An hour of time is gained as though time is nothing, jarring the world of this city. A moaning starts in the streets, as people wonder what to do with this extra hour. The Republic is ending, I remind them. Civilizations end stealthily, not suddenly. On the last day of November, a chilled wind enters the city. The next morning, there is frost. Venice glitters like a jewel. A cold, desolate fake. The first week of December, I witness snowfall. The flakes are light and powdery as they tumble. A week later, the edges of the canals are crusted with ice.

When the towers freeze, the clocks stop. Time has ended, I think, as I walk with my cane and my jacket and my thick gloves, as though we have replicated Montreal in Europe. It is just a matter of time before a skiff passes and throws salt onto the cobbles.

A storm of snow arrives, and the taxis stop. The gondolas are moored. In churches, men and women sing songs of God. Bless me, Ruth. You said a crisis was coming to this city, to us. Oleg said it was foretold, as though I should have known. Now we freeze in this city that was once so full of heat, oscillating between extremes, stuck to a pendulum, moving back and forth.

The canals freeze over the day after Christmas, during a snap that reduces the city to a full stop. People tuck wine bottles under their clothes. There are no cars here, no roads. And now, no water.

A thousand at a time, people leave the city. A year at a time, empires crumble, a descent so slow that it’s hard to stop. How can the canals freeze, people ask? We were warned, I tell them. Decades ago, we were warned, but I didn’t listen, either.

The palazzo drips water as the snow on the roof melts in the sun, then freezes again. The droplets tumble through holes I can’t find, weaving their way through the cracks in the floorboards, into the basement. There, they gather on the ice and create stalagmites. Spires grow at the bottom of my home. I move between them. A cane raps at the ice. Beyond the spires, I move onto the ice of the canal. Thick. Unyielding. Permanent.

It’s night. I stand on a canal of Venice.

There are shadows in the windows. Candlelight is better than light bulbs, because the latter have become so efficient that they give no heat. People in candlelight lean against the frosty windows and look down on the old unwell man with the cane, in front of his leaking palazzo. What is wrong with him, they wonder? When did his crisis begin?

So long ago, I say to the icy wind. Mine coming to a close, as this other one springs from the burial shroud.

A week later, parcels arrive in my palazzo. I bought many pairs, mostly in sizes fit for children, but one is for me. I put them on and test the blades against the ice. They catch, and cut. They slice. I put away the cane and slide, so easy. Along the canals of Venice, I glide in my coat and gloves, my red hat, until I reach the Grand Canal. Under the Ponte dell’Accademia I slide, amazed at how it looks from down here. People are pointing. Who is this man, they say? What is he doing? Doesn’t he know that this is a crisis?

We were warned, I tell them. Now look here.

Faster. Fear not the ice or its solidity. Worry not one bit about this patch of settled snow or the roughness it may conceal. Avoid the moored gondolas and the piers turned crystalline in the chill. I visit the city where I have decided to end my times. At the canal next to the Libreria, I take off the skates and walk into the bookshop. Electric heaters blow air. In the courtyard, books sag with the weight of icicles, as children step atop the platform. Eroded letters are frozen together at the base of the books, whole novels plastered by the cold.

I teach people how to skate. I give them their own blades and tell them to be careful. Guard your heads. Watch out for rough patches. One man delivers food on his skates; a woman pulls a steaming black robot on a flat board to sell espresso. But mostly it’s the children that play, whipping between buildings that are still sinking but more slowly now, as though the city is being preserved. The children skate effortlessly as I weave amongst them, breathless and old. My problems are ending on the ice. I’ll be buried on the mainland, like Oleg, when the time comes. The crisis before these children, though—that is just starting.

***

You tell me to come with you, that you want to show me something.

In an old villa, you open a door and we climb down a ladder to a floor of dried dirt. Around us are stone pillars holding the villa up, their ends punctured through the dirt.

“You wanted to know what holds Venice up,” you tell me. “They are tree trunks, piled into the ground to the clay that lies underneath the silt. They are made of oak, a wood that resists water. There is no air under water, and thus no rot.”

“But this is stone, Ruth,” I tell you. In the gloom from a single lightbulb, the pillars look like they could hold up the whole world.

“I was here when the trees were piled into the earth. And I came back often, to watch them petrify and turn into stone. Wood turns into stone. Doges turn into nothing. And we,” you say with a smile, “become friends in Venice. Tomorrow, you are going to leave, and we are going to wonder if we will see each other again. Come back here, and maybe we will.”

We go to the Bridge of Sighs, named for the final breaths of freedom issued by convicts headed for jail. We stand over a canal, next to each other, but I imagine a Venice where all the water has left. Below, there is a chasm leading to the hard dirt, and people are walking along the edges of the canals, careful lest they fall from these cliffs. In some places, ladders have been strung to the bottom, and people have climbed to the hardness. Couples go to the petrified stone pillars that hold up Venice, a city now floating in the air. They bring tools with them so that they can write their initials in the foundations of the city.

“What do you see down there?” you ask me.

***

I come to Venice a fifth time. I’m a hundred years old. I sold the palazzo, as I could no longer take care of it, but I still come here, a tourist. Sometimes, I visit Oleg’s grave. But mostly, I look for you in this most serene city.

A horse pulls me in a gondola on the ice. The rider is in a fur coat, singing. She takes me to the edge of the Grand Canal. There, in the distance, is a mountain of frozen water, tectonic plates of ice that have crashed together and jutted skyward to be smothered in snow. Cables carry tourists to the top of the mountain. People ski down, then skate to the city.

“They say it’s not sinking anymore,” I say to the driver.

“Oh, it is, it is,” she returns. “But so slowly, you would not even notice.” She sings a happy song about how the ice has come, sent by a force that no one could imagine, to save this place from sinking. This land that was once an empire. A Republic.

About the Author

Trent Lewin is an East Indian immigrant environmental engineer living in Canada. He has won the Lascaux Prize in Fiction, the New Ohio Review's Annual Fiction Contest, and Boulevard's Emerging Writers Contest, and been a finalist in the Arts & Letters Fiction Contest. He’s also been published in december Magazine, Grain, Ex-Puritan, The New Quarterly, and FreeFall, and been shortlisted by the CBC Short Story Prize and the Commonwealth Writers Prize. Trent has a Distinguished Story in the 2025 'The Best American Short Stories.'

about the artist

Haley Cole is a visual artist in Colorado. Her work explores archetypal themes and timeless narratives, often blending the mythical with the modern. Rooted in the artistic legacy of her mother and grandmother, Haley seeks to bridge the past and present through bold, expressive creativity. Her art has been featured in Tint Journal, Kitchen Table Quarterly, The Freshwater Review, and more.