The Effects of Collagen

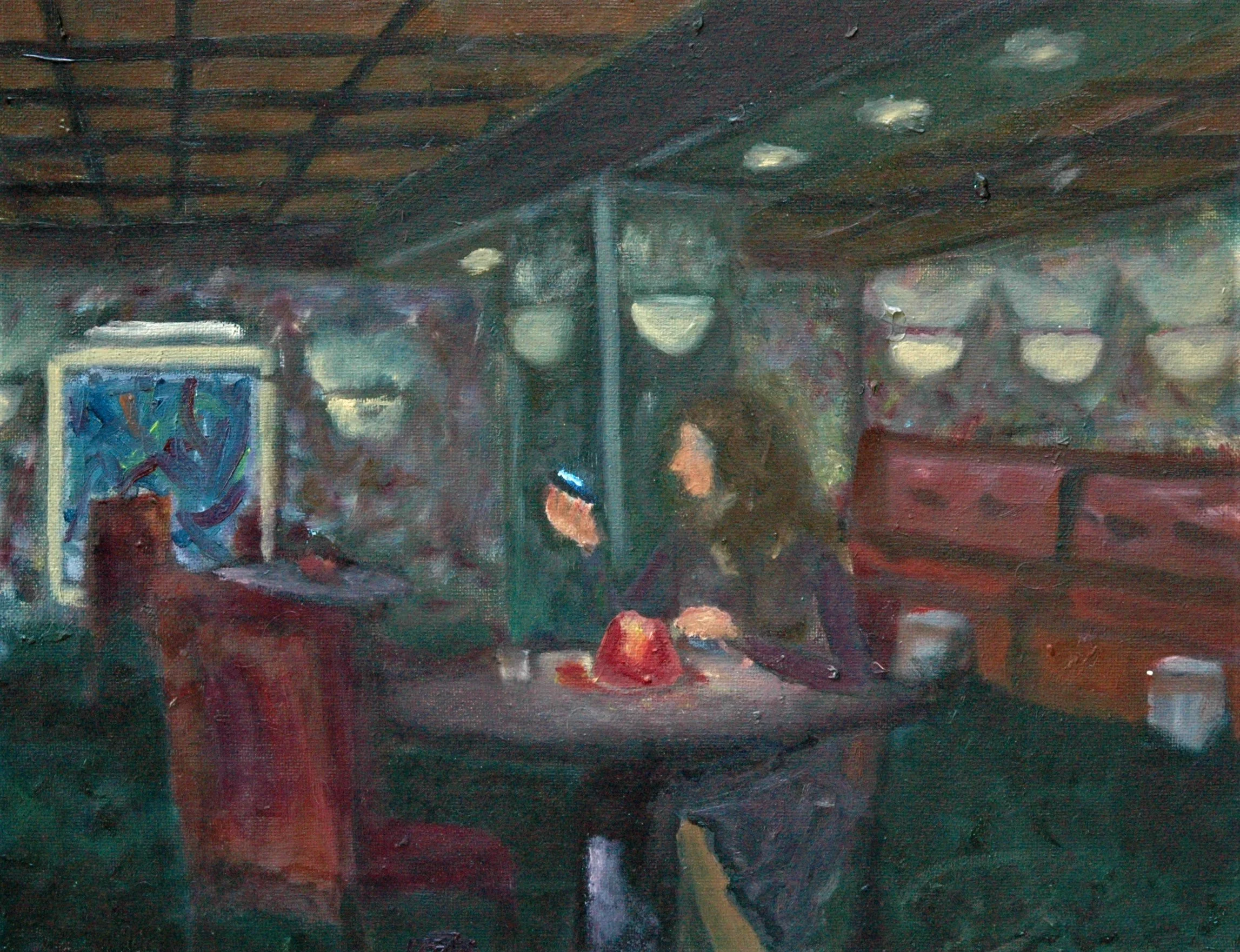

“Cellar” by M Patrick Riggin

On Lan’s date with her first match on Tinder, Lan’s mother calls to tell her that her grandpa had passed away in the hospital a few hours ago and they are flying to Shanghai for the funeral. Her parents have already bought flight tickets to leave the next day, and Lan is across the country sitting in a hipster mifen noodle restaurant, waiting for her date to arrive. She recognizes him from the hair, spiky yet somehow windswept, but his face seems less bright than in the profile photos of him posing against a pillar at Stanford. He sits across from her and Lan passes the menu.

“Apparently the beef mifen is the classic. I’m getting the beef tendon version,” she says.

Grandpa used to make the best beef tendon. He cooked the tendon for hours until it softened and gelatinized to the extent you didn’t need to chew, you could simply swallow. He even knew how to make the super thin mifen which Lan could never find at restaurants. They only served the thick, bouncy noodles where the flavors slipped right off unless you simultaneously ladled the broth into your mouth with a soup spoon. When they ate, Grandpa slurped so loudly Lan couldn’t hear her own slurps. Lan’s mother gave Grandpa the evil eye, not that he could see. Lan’s mother was big about table manners even though Grandpa kept telling her the louder you slurped and chewed, the more you enjoyed the food. Lan mimicked Grandpa, smacking her lips against the noodles and stretching her mouth open and close to chew the beef, and her mother knocked the chopsticks out of her grip. “Eat like a normal person or don’t eat at all,” she told Lan.

Lan glances down at her phone and notices her date’s socks first: one patterned with rainbow unicorns and the other with pink hearts.

“Cool socks.” Lan means it. She wishes she owned more interesting socks beyond the same stripe-patterned Adidas pack from Costco.

“Thanks, these are kind of magical, actually. I sprained my ankle during an ultimate tournament while wearing them, and after, all sorts of good things started happening. Like an acquaintance from the women’s team offered to go grocery shopping with me and I managed to walk the whole mile and a half on crutches.”

“Are those your only pair of magic socks?”

“I also have Einstein special relativity socks. When I wear one of them, I do well on tests, but they don’t work outside of that scenario. I may even be dumber in general on the days I wear them.”

Lan’s only memorable piece of clothing is the wool sweater Grandma knitted with grey and purple floral designs covering the entire body. “It’s an old people sweater,” Lan’s mother had said. “If you aspire to be a young professional, you should be wearing single colors, preferably black. That makes you look thinner and sleeker.” The wool grandma used was too itchy to wear anyway. Lan could only wear it in the winter when it was cold enough and she needed to double layer with a long-sleeved shirt underneath. Grandpa told her she looked cozy, wrapped like a salted piece of pork pillowed and cushioned by glutinous rice. “Not like an old lady?” Lan had asked.

“Nonsense,” he’d said. “Look, you’re still so little.” Grandpa lifted her from the armpits and spun her around. She had been eleven and was afraid she’d gotten too heavy and would dislocate his arms, but he had worked as a mechanical engineer and was used to lifting planks of wood and bricks. She liked to poke his biceps and marvel at how rocklike they were.

The waitress places two steaming bowls of noodles on their table and hands them ladles and chopsticks. She also hands them each two small bowls of chili oil and Chinese black vinegar. Lan shakes her head. She can’t handle spice.

“What’s the best thing that has happened to you while wearing the socks?” Lan asks as she stirs the toppings of pickled radish and thinly sliced brisket into the soup.

He claims the socks got him out of a hairy situation in which someone thought he was trying to steal their bag of heroin when he was only trying to rush to a wisdom tooth removal operation. She nods along.

“Ouch, those wisdom teeth are excruciating..” Lan places a chopstick-full of noodles in her ladle and spoons it into her mouth, trying to avoid slurping.

Lan had her wisdom teeth removed years ago. Grandpa was the one who suggested it. His teeth were horrible, plagued with gum recession and cavities on most molars. “We don’t get regular cleanings like you do here in America,” he said. “We went to the doctor when we had a problem, not before. Granted, it also didn’t cost a fortune.” After the surgery, Grandpa fed her soup and millet porridge. He cut bits of duck into microscopic pieces she could swallow and mashed taro with sugar and coconut milk for dessert. She complained every day about the pain but the sweets made her suffering partially worth it. Grandpa never made anything sweet besides sliced starfruit with granulated sugar on the side for dipping. “It’s the one thing he does right,” Lan’s mother had said when Lan could no longer fit into her mother’s old qipao.

“Yeah, and now my socks are quite dead and need patching, but I’m not sure how to fix them. According to my art friend who deals with textiles and stuff, I should probably find a stretchy material, maybe an athletic shirt. But all my athletic shirts are in a wearable state and I don’t want to cut them apart.” He jams a piece of flank and silver skin in his mouth. Lan feels her phone vibrate and glances down. Her mother has sent a screenshot of return flight tickets with a layover in California to visit, drop off some green tea, check out Lan’s newly upgraded apartment which she hasn’t truly upgraded. She still lives in the termite-infested complex and uses a room divider to block out the worn and chipped walls when she video calls her parents, lying about the new amenities and gym and high ceilings in this made-up new apartment construction.

“Sorry, what was that?” Lan asks, pushing a strand of hair behind her ear. Her mother says this gesture makes her look demure and agreeable like she’s made of rice paper meant for plating and not for wrapping.

“Do you play sports? Got an athletic shirt to spare?”

Lan doesn’t play sports. At least, she doesn’t consider herself an athlete although she had dabbled, as every young girl once had, in ballet. When Lan was eight, her mother had also signed her up for swimming to build strong lungs and tennis to develop power. Lan preferred playing badminton with Grandpa, although her mother deemed it a “fake” sport and refused to pay for new rackets or birdies, so she and Grandpa used the same old birdies even as their feathers frayed and they no longer soared through the air as they used to. Lan got good at slamming the birdie fast and hitting it in hard-to-receive positions, although Grandpa was always better. “You might as well play tennis,” her mother said. “It’s the same thing. But physically challenging and worthwhile.”

“Nah, I don’t have any of the polyester stuff.” Although maybe she does. Maybe her mother bought her one of those Nike shirts years ago when Lan was supposed to join the senior varsity track team before she hurt her knee and her future in competitive sports. Grandpa made her a big bowl of beef stew that day, lecturing her about the importance of collagen on her healing joints—it keeps you all stuck together and mobile, like a properly pulled Liang pi. But her mother remained convinced Lan could get back up. Her mother thought there wasn’t anything doctors couldn’t fix: they’d sewn her stomach back together after Lan was pried from her body; they’d tossed her tiger balm into the trash and introduced her to hydrocortisone; they could make Lan run again like lightning catching up to you on the highway. Lan’s mother knew the real miracle workers were the doctors.

There’s an eyelash-length piece of cow hair in Lan’s beef tendon. Grandpa always plucked out any lingering hairs with tweezers. But Lan hates wasting food and closes her eyes as she eats it. She can pretend it doesn’t exist. It’s impossible to pick up on the texture of such a microscopic piece of hair anyway. She swallows.

“That’s a shame,” he replies. “I’ll ask my art friend then. She probably has something. Her closet is full of random clothing.”

“Her closet?”

“Oh yeah, she’s my roommate, but don’t worry, we’re just friends, haha.”

The waitress brings them the check as Lan finishes sipping the broth. She likes clean soups with a heavy dose of MSG.

“Should we split the check by dish?” He asks. Lan wonders how much a flight from California to Shanghai would cost, how many layovers would that be, if there was one available in the next twelve hours. She tosses her credit card on the table. “It’s okay, we can just use my card.”

“Then I’ll Venmo you? What’s your username? You want to calculate the proportional tax and tip amounts?” He asks, but Lan is already walking up to the cashier with the order and credit card, fast-tracking the return of a receipt that she pockets before exiting, door slamming in her wake. Grandpa wouldn’t have minded. “Most men aren’t great once you get to know them, so you aren’t missing out,” he told her senior year when she cried about being the only one not asked to prom. Then he took her to the park where they sat on the swing set, marveling at how loudly it creaked, how fast she’d grown up.

About the author

Lucy Zhang writes, codes and watches anime. Her work has appeared in Black Warrior Review, The Cincinnati Review, West Branch and elsewhere. Her work is included in Best Microfiction 2021 and Best Small Fictions 2021. Find her at https://kowaretasekai.wordpress.com/ or on Twitter @Dango_Ramen.

about the artist

M Patrick Riggin is a Pittsburgh-born writer, artist and musician. While attending college for history and journalism, M Patrick worked as a musician and freelance artist. Restoration, leathercraft and gardening are hobbies that contribute to his art. To follow his artistic journey, he can be reached at mpatrickriggin.com.